The Current View Tool (CVT) is a widely used clinician-rated tool for capturing the problems and situation of a child or young person. Here Chloe Gathercole, Dr Tim Clarke, Sophie Allan, Dr Brioney Gee and Maddie Johnson present an innovative project using the CVT to inform transformation of child and youth mental health services in Norfolk and Waveney.

What question or questions were you trying to answer? What was your intention?

For many years, we had been keen to investigate the presenting problems and general complexity of service users across child and youth mental health services in Norfolk and Waveney. We were interested in investigating this across providers for those with mild to moderate difficulties and those for more complex and severe difficulties. There were many reasons that we were keen to investigate this. In particular, mild to moderate providers were reporting seeing young people of greater complexity than expected. The results would inform the child and youth mental health service transformation currently taking place across the region.

How did you go about this?

We used the CVT (available at https://www.corc.uk.net/outcome-experience-measures/current-view/), which is a clinician-rated tool for capturing the problems and situation of a child or young person. It includes provisional problem descriptions (e.g. social anxiety, psychosis), complexity factors (e.g. young carer, autism), and contextual problems (e.g. at home, school or in the community).

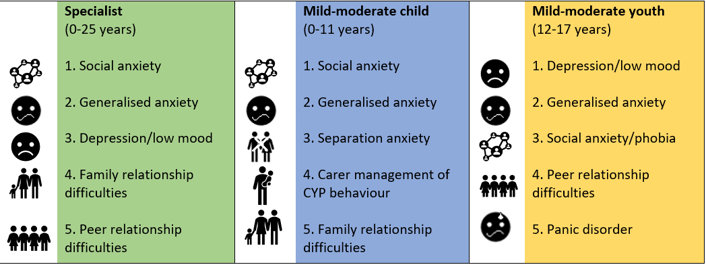

The project took place across three providers who worked with children and young people from 0-25. The three service providers consisted of 1) specialist, 2) ‘mild-moderate child’, and 3) ‘mild-moderate youth’. The names of providers are withheld for anonymity.

For all clinicians, we randomly selected 20% (or a minimum of 5 cases) across their caseloads to complete the CVT for. If any selected cases were not deemed suitable (e.g. had been recently discharged) then an alternative case was randomly selected.

Clinicians were provided with information and resources, such as the CVT user guide. Prior to COVID-19 restrictions, the CVTs were completed on paper, manually scored and entered onto a database. Following restrictions, with permission of the CVT authors, we transferred the CVT items onto Microsoft Forms. This allowed for remote completion and automatic database entry.

The Current View tool does not have subscales currently. To analyse the data, we added up scores (using none=0, mild=1, moderate=2, severe=3 and yes=1, no=0) to make total scores.

What did you find out?

Clinicians filled out 663 CVTs. A key finding was that, regardless of provider, young people presented with multiple conditions and significant complexity. Only six young people had one type of difficulty reported (0.95%). Further, 335 had more than ten types of difficulty reported (53%).

See here the top five provisional problem descriptions for ‘specialist’ (green), ‘mild-moderate child’ (blue), and ‘mild-moderate youth’ (yellow) service providers.

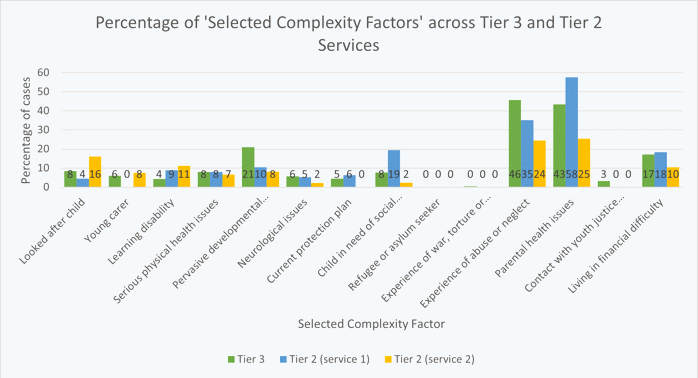

Considering the different service provision, we expected to find that the specialist provider would be seeing patients with more presenting problems and higher complexity than both mild-moderate providers. In terms of the ‘total CVT score’, using one-way ANOVAs we found that the specialist provider was seeing cases with significantly higher scores than the mild-moderate child provider. However, we found that specialist and mild-moderate youth providers were seeing service users of similar complexity.

When we broke ‘total CVT score’ down, and looked specifically into the ‘Selected Complexity Factors’ score, we found the opposite pattern of results. The specialist provider was seeing service users with more selected complexity factors (e.g. abuse, trauma, parental health difficulties) than the mild-moderate youth provider. However, the specialist and mild-moderate child provider are seeing service users with comparable numbers of selected complexity factors.

Are there any key limitations to this work?

One limitation is that there is no guidance on scoring the CVT.

Another limitation was the response rate, which was 63% overall. Response rate varied dramatically across different providers. The mild-moderate youth provider had the highest response rate (95%). The specialist provider had the lowest response rates, which could reflect service pressures and staff capacity.

Why is this work important? What do you hope its impact will be?

A report was written, and the findings are being used in to inform service planning decisions.

Based on the finding that the specialist and mild-moderate youth providers are seeing cases with similar ‘total CVT scores’, clearer pathways through care may be needed. This might include a review of safe and effective escalation from mild-moderate to specialist services when necessary. Joint pathways across providers with increased communication would address this.

The findings also indicate that services for younger children should offer interventions that target attachment difficulties, separation anxiety and carer management (e.g. Solihull Approach, Parent-Delivered CBT). It goes without saying that we need to ensure clinicians have adequate training in such interventions. Shared training across providers may be cost effective and enhance joint working.

There were similar numbers of ‘Selected Complexity Factors’ (e.g. abuse, trauma, parental health difficulties) between specialist and mild-moderate child providers. It may be that a proportion of these children develop further difficulties and are later supported by specialist providers. Supporting families to access mild-moderate child providers could prevent future development of mental health difficulties. Joint working with social care/Local Authority will be key in the early support of families.

We have found the CVT to be extremely useful in assessing and presenting problems and complexity of service users. Other mental health providers wishing to engage in service transformation or improvement projects could consider adopting a similar methodology. Routinely using the CVT at initial assessment and inputting the data into an electronic patient record system would make this process easier.

Many thanks for this summary to:

Chloe Gathercole - Assistant Psychologist at Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust (NSFT). Chloe drove the initial project dissemination and coordination, as well as gathering and inputting data from CVTs filled out by staff.

Sophie Allan - Trainee Clinical Psychologist at the University of East Anglia. Sophie, as well as Dr Brioney Gee and Maddie Johnson supported the project.

Dr Tim Clarke - Principal Research Clinical Psychologist (NSFT) and Children and Young People’s Mental Health Clinical Advisor (East of England NHSE/I). He led the project.

For more information on the project, contact Tim Clarke timothy.clarke@nsft.nhs.uk